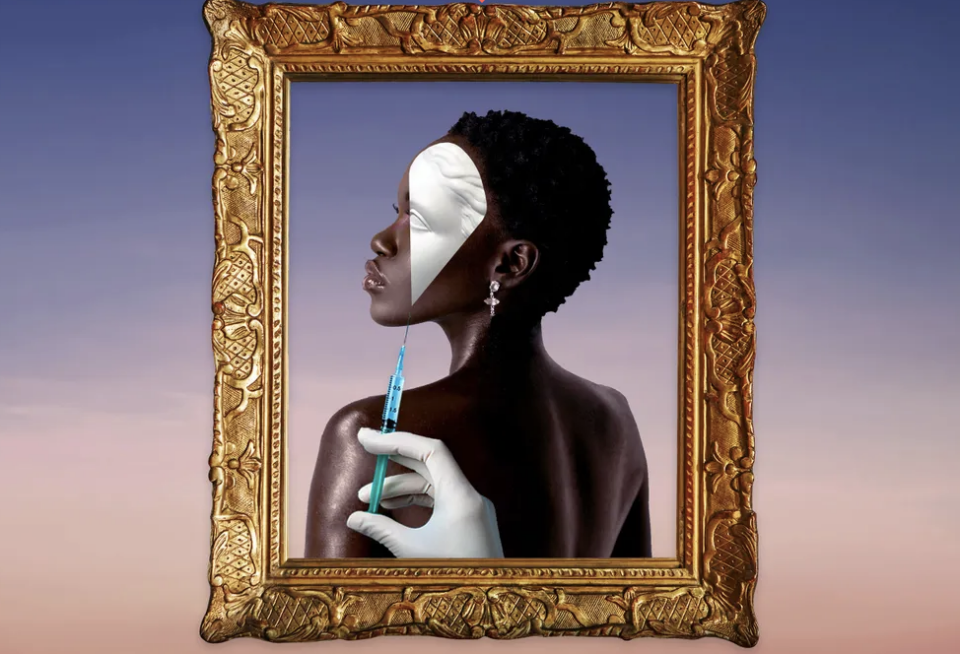

Black Americans Are Getting Botox More Than Ever

Ruth Samuel

Black Americans are letting go of the stigma behind getting work done from past generations and smoothing, filling, and fading with abandon.

This story is a part of The Melanin Edit, a platform in which Allure will explore every facet of a melanin-rich life — from the most innovative treatments for hyperpigmentation to the social and emotional realities — all while spreading Black pride.

Dermatologist Corey L. Hartman, 46, receives Botox every three to four months and has been doing so since his residency 15 years ago.

“If I have heartburn, and I know that there is a fix for heartburn, I’m going to go and get the fix for heartburn. If I have a line in my face that I don’t like, and I know that there’s a fix for that line, then I’m going to go get the fix if I can afford it,” Hartman says.

As the founder and medical director of Skin Wellness Dermatology in Birmingham, Alabama, Hartman said he has seen a huge increase in the interest, discussion, and follow-through of Botox and other injectables among Black and brown patients.

Hartman says, “This has become a topic that is now socially acceptable across the board. Now you have [people] bringing their girlfriends in and having events at doctors’ offices or Botox parties. Generation X and the baby boomers look at this as something corrective and the millennials and Gen Z are looking at this as self-care, preventive medicine.”

Growing up in a Black household in New Orleans, Hartman recalls hearing from an aunt that “Black people don’t go to the dermatologist” because Black folks are blessed with so-called good genes, catering to the old adage “Black don’t crack.” He said that a major issue with injectables is representation in marketing and how social media has skewed the perception.

“You can’t be it if you can’t see it. The marketing behind a lot of these procedures, when they were first introduced, was only to white women, and the studies were only conducted on white women,” said Hartman.

The Ongoing Rise of Botox

Per the American Society of Plastic Surgeons’ (ASPS) 2020 Plastic Surgery Statistics Report, more than 15.5 million cosmetic procedures were performed this year alone, with nearly 13.3 million being minimally invasive.

The top five cosmetic minimally-invasive procedures were Intense Pulsed Light (IPL) treatment (827,409 procedures), chemical peel (931,473 procedures), laser skin resurfacing (997,245 procedures), soft tissue fillers (3.4 million procedures) and, in first place, botulinum toxin type A (4.4 million procedures). Botulinum toxin type A is often referred to as “Botox,” which is actually the name of the most commonly recognized injection brand. However, there are other botulinum toxin type A injections like Xeomin and Dysport.

And while the majority of those weren’t performed on Black patients (the ASPS found that only 11 percent of total cosmetic procedures in 2020 were done on Black patients and only 4 percent of botulinum toxin Type A injections), that particular group’s interest in these types of procedures is rising. According to the ASPS’ 2020 Plastic Surgery Statistics report that breaks down procedures among ethnicities, 1.78 million Black Americans opted for cosmetic procedures last year and the numbers have risen annually, from 1.68 million in 2018 to 1.77 million in 2019. While “Black don’t crack” may be tried and true for some, many are taking beauty into their own hands. The lingering question is why.

Saedi says that although Instagram and Snapchat filters have contributed to unrealistic standards, social media has also played a role in democratizing access to beauty knowledge and information. Historically, cosmetic treatments and enhancements have been seen as procedures reserved for the white, affluent, and vain, but that is quickly changing.

Why Some Black Folks Want Botox

When it comes to the perception that only the wealthy white people get non-invasive treatments, that fact is slowly shifting. It should be noted that a significant racial wealth gap still persists in the United States. According to U.S. Census figures released last year, the median income of Black households in 2019 was approximately $45,000; that’s about 45 percent of the median white household income. Despite this financial inequality, Black people still seem to find ways to fund their “tweakments.” “I don’t think it’s a money thing. People are gonna find the money for things that they want to do,” says Hartman.

Now, users can see that these procedures are “not just for sun-damaged, Caucasian skin with lines,” says Saedi.

Aging in patients of color looks a little different. Because of the extra melanin, photo aging occurs more slowly, but you might see dullness, hyperpigmentation, and sagging, and there are things that cosmetic treatments can do to help. “In, Black patients, they typically don’t have skin that manifests with wrinkles with aging, and they don’t really have forehead lines,” says Nazanin Saedi, who currently sits on the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery’s board of directors. “You see [11 lines between the brows] more than you see forehead lines. Whereas commonly, in someone who’s the same age who’s Caucasian, they would have lines across the forehead as well as the 11 lines. If you were to look at Asian populations, they tend to get crow’s feet.” Black patients also tend to deal with hyperpigmentation, hollowing around the eyes, and sagging of the skin around the mouth as signs of aging.

Saedi, who is of Persian descent, has over 12 years of experience in the field and has been getting Botox since her late 20s. “Botox is a botulinum toxin that basically relaxes muscles that move. It helps areas of movement so that you don’t scowl or you don’t move your forehead a ton to create those forehead lines, whereas filler is great for replacing volume that’s been lost,” says Saedi. She views it as a form of “prejuvenation,” starting younger with smaller amounts of Botox to avoid heavy lifting later — and she’s not alone.

Hartman says that at age 22, collagen levels peak; for every year after that, you lose 1 percent of that collagen. Though Black people don’t age in the same way as those with less melanin, dwindling collagen results in significant volume loss. If applied to the three indicated areas — crow’s feet, between the brows, the forehead — Hartman said the average Botox procedure for those areas could cost approximately $780 three or four times a year.

The Patients

Twenty-two-year-old Chloe* is willing to pay the price. In fact, she’s paid over $2,000 in the last two years on noninvasive treatments. The young consultant, whose father is Ghanaian and whose mother is white, was frequently told throughout her life she didn’t have distinctly African features, such as high cheekbones, and has received filler to supplement that and prevent smile lines.

Chloe says most of the people in her social circles lean against cosmetic treatments, arguing “you don’t need it.” “A lot of people think that it’s in vain,” Chloe said. “There is an unfair expectation that Black women have to be effortlessly perfect because there’s just this idea that if it’s not natural, then it’s not valid. If you look at where all the attention, praise, and adoration is going, it’s to the people that aren’t natural.”

Even though Black skin doesn’t age as quickly as others, Black influencers still face pressure to look perfect. Aesthetician Sean Garrette is known on Instagram for his glowing complexion. Spending each day filming or shooting content, tutorials, and interviews, he can sense when negative habits creep in because “he sees things that I don’t like that other people don’t see.” The 29-year-old recalls growing up in a family that was very conscious about appearance.

Now based in New York City, he says the most pressure he felt to keep up appearances was while living in Los Angeles as a gay Black man. He received under-eye and nasolabial filler for smile lines.

“You see a lot of different types of people and ethnicities in New York. In L.A., it’s almost like one standard of beauty. For men, especially Black men, you’re almost fetishized in Los Angeles. You’d have to have washboard abs, a small waist, again, thick, gorgeous hair, beautiful bone structure, great clear skin. I’m none of those things,” says Garrette.

He said his provider has been excellent while quite conservative in her work, counseling him to not be over eager in fixing issues that don’t exist. What remains important is having a doctor who has your best interests at heart, whether you elect for Botox to prevent sweating in glands, address temporomandibular joint dysfunction, or simply cosmetic purposes.

Thirty-nine-year-old Danielle Gray is a skin-care influencer based in Queens, New York, and it took time before she found a dermatologist she could trust.

Gray said, “A dermatologist reached out to me because I might have written something about wanting laser hair removal. What was most uncomfortable was that afterward I realized she had burned me and parts of my skin had hyperpigmentation.”

Despite advances in technology, this is a symptom of some dermatologists’ inability to treat Black skin. Dermatologist Carlos A. Charles is the founder of Derma di Colore, a practice based in New York City that seeks to provide care with an emphasis on melanin-rich skin. Charles says the disparity is multifactorial and could be attributed to a lack of training.

“Historically, if you look at textbooks — a lot of the disease processes and the pictures just going through it — things are described typically in lighter skin tones and white skin tones. That creates a little bit of a blind spot because things can look different on darker skin,” said Charles.

Now, Gray’s dermatologist is Michelle Henry. In 2018, Gray received filler to address undereye hollows; one year later, she received Botox from Henry after noticing some fine lines and shared her journey online. For Gray, she believes it’s important to have a Black dermatologist because of their expertise: having someone who goes through the same issues and who understands how it will be perceived. On one of her Instagram posts, she remembers one user commented “you need to age gracefully like these Black celebrities do.”

“Just because [celebrities are] not telling you what they get done, that doesn’t mean they’re not getting it done,” Gray says. “To be quite frank, I think it is all bullshit. People do not know what they want. People will tell you, ‘oh, you should wear your natural hair, you should do everything natural.’ Then when you show it to them, they’re not here for it.”

But despite the negative comments, Gray isn’t phased. She’s happy in her choices to venture into aesthetics. “I don’t have a fear of aging because I feel like, the older I get the more self-aware, the more self-esteem, the more self-confidence I have. I’ve learned early on to not really pay attention to what people say. I just look for my community.”